[ VC&G Anthology ] The Making of Pong (2012)

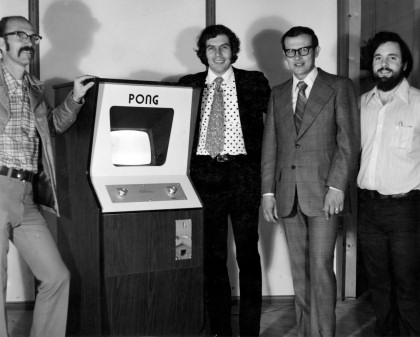

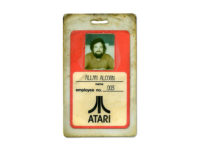

November 29th, 2022 by Benj Edwards Atari founders circa 1972-73 (from left to right):

Atari founders circa 1972-73 (from left to right):

Ted Dabney, Nolan Bushnell, Larry Emmons, and Allan Alcorn

[ Atari Pong turns 50 years old today, and I thought it might be fun to revisit an article I wrote about the game’s creation for Edge Magazine (Issue 248) back in 2012. Since the web version of that piece is no longer online and I retained the rights, I am republishing it here. –Benj ]

Forty years ago this November, Atari introduced the world’s first video game sensation, Pong. The game, while not the first of its kind, would provide the economic catalyst necessary to jump start a completely new industry.

In 1971, Nolan Bushnell and his partner Ted Dabney created the world’s first commercial arcade video game, Computer Space, for California coin-op manufacturer Nutting Associates. It made a minor splash in the arcade market, but it was not wildly successful.

In 1971, Nolan Bushnell and his partner Ted Dabney created the world’s first commercial arcade video game, Computer Space, for California coin-op manufacturer Nutting Associates. It made a minor splash in the arcade market, but it was not wildly successful.

For round two, Bushnell wanted to follow up with a driving game for Nutting, but he quickly found himself at odds with Nutting’s executive staff about the direction of the company’s video game products. He resigned from the company, taking Ted Dabney with him.

Bushnell began to shop his driving game idea around to other American coin-op makers. Bally, then the largest arcade amusement company in the US, showed interest in the idea. The firm awarded Bushnell and Dabney — then doing business under a partnership named “Syzygy” — a contract to develop a video game and a pinball table. Syzygy would create the video game design and license it to Bally, who would produce the hardware and sell it under the Bally name.

Under the new contract, Atari received $4,000 a month to develop the two games, which gave just enough financial room to hire an employee. Recognizing his limitations as an engineer, Bushnell reached out to Allan Alcorn, a former colleague from Ampex, and asked him to join the company.

Under the new contract, Atari received $4,000 a month to develop the two games, which gave just enough financial room to hire an employee. Recognizing his limitations as an engineer, Bushnell reached out to Allan Alcorn, a former colleague from Ampex, and asked him to join the company.

Alcorn, then 24 years old, accepted the offer to work for Syzygy in June 1972. It was a risky move at the time, but after a few years at Ampex, Alcorn had grown bored with his work. He was ready for a new challenge at a startup company, and both Bushnell and Dabney recognized his considerable talents as an engineer.

That same month, Bushnell and Dabney incorporated their company under a new name, Atari, Inc., and set out to change the world of arcade entertainment forever.

Designing Pong

After joining Atari, Alcorn’s first task was to examine the design of Computer Space and learn how it displayed movable images on a television set. Alcorn admired the ingenuity of Dabney’s motion circuitry design, but the schematics were a little too messy for his liking, so he built his own version based on Dabney’s concept.

Since Alcorn was new to designing video games (and who wasn’t), Bushnell decided to assign him a warm-up exercise to test his skills as an engineer. As it turned out, the video game design Bushnell suggested to Alcorn wasn’t an entirely original one.

Sanders Engineers Bill Harrison and Bill Rusch in the 1960s.

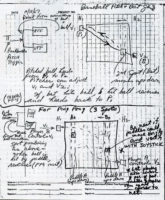

One of those engineers, Bill Rusch, had designed an electronic table tennis game while brainstorming new game ideas. He sketched out his creation in a memo dated October 18th, 1967. The game was simple: it involved two player controlled spots, which served as paddles, and one machine controlled spot, which served as a ball. One player would serve the ball, and the other would try to return it by hitting it with his paddle. If he missed, the other player would score a point.

Having been designed in 1967, this ping-pong game (which would later become part of the Odyssey system) eschewed electronic luxuries like sound effects or an on-screen scoring system. During its development, project leader Ralph Baer and his team kept costs low because they intended to license their design for sale as a home consumer electronics product.

When it came time to assign Alcorn a test project, Bushnell recalled the ball-and-paddle game he had seen at the Magnavox event. He told Alcorn that Atari had obtained a large contract with General Electric to develop a home video game console. Bushnell laid out the basics of the game he wanted, describing a game very similar to the Magnavox ping-pong game, but adding one detail — it would have an on-screen score display.

When it came time to assign Alcorn a test project, Bushnell recalled the ball-and-paddle game he had seen at the Magnavox event. He told Alcorn that Atari had obtained a large contract with General Electric to develop a home video game console. Bushnell laid out the basics of the game he wanted, describing a game very similar to the Magnavox ping-pong game, but adding one detail — it would have an on-screen score display.

Because Alcorn had thought his game would become a home game console, he tried his hardest to keep the game fun and the cost of parts low. First, he put up a spot on the screen, then added some paddles. Along the way, Dabney and Bushnell would play it and offer suggestions.

Alcorn deviated from Bushnell’s basic design with his own innovations. First, he divided each player controlled paddle into eight logical segments. Upon hitting the paddle, the ball would bounce off of it at a different angle depending on which segment it hit.

Amazingly, the Magnavox game did not incorporate this feature. Instead, it allowed each player to slightly move the vertical orientation of the ball with a second knob (marked “English”) on the Odyssey’s controller.

Amazingly, the Magnavox game did not incorporate this feature. Instead, it allowed each player to slightly move the vertical orientation of the ball with a second knob (marked “English”) on the Odyssey’s controller.

Alcorn’s second major innovation was to speed up the movement of the ball as the game progressed. During long volleys, gameplay would get more intense as the ball became harder to hit. Scoring a point would reset the game back to normal speed.

In another major deviation from the Odyssey game, Alcorn’s design treated the top and bottom of the screen as walls. If hit, the ball bounces off these invisible walls instead of flying off the “court” in the Odyssey version.

As a finishing touch, Alcorn wired in a rudimentary sound effects system that created memorable “pong” sounds when the ball bounced off the paddles or walls. Those simple sounds seemed to bring the game to life in a way that the silent Odyssey game couldn’t match.

Drowning in Quarters

While Alcorn perfected his design, Bushnell still had his heart on a driving video game. The co-founder had intended the ball and paddle game to be a one-time throwaway test of the engineer’s skills. But after about a month’s work, Dabney and Alcorn found that Alcorn’s “throwaway game,” while simple, was a total blast to play. It was then that Dabney and Alcorn decided, independently of Bushnell, to turn the ball and paddle game into a real product.

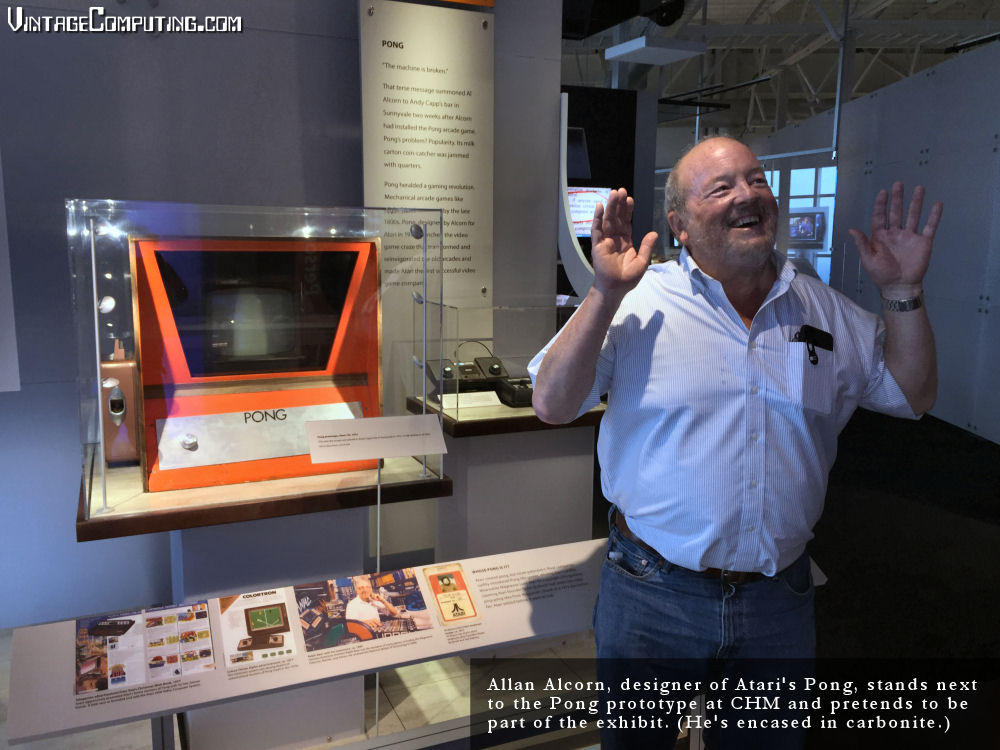

Alcorn and Dabney stuffed the ball and paddle prototype circuitry and a TV set into a rudimentary wooden cabinet with a coin box on the side that Dabney built. After some more pestering from his colleagues, Bushnell realized that the game was worth pursuing as a product, and the trio brainstormed names. They christened the game “Pong” in honor of its ping-pong roots and placed the prototype in a local bar called Andy Capp’s Tavern.

Alcorn and Dabney stuffed the ball and paddle prototype circuitry and a TV set into a rudimentary wooden cabinet with a coin box on the side that Dabney built. After some more pestering from his colleagues, Bushnell realized that the game was worth pursuing as a product, and the trio brainstormed names. They christened the game “Pong” in honor of its ping-pong roots and placed the prototype in a local bar called Andy Capp’s Tavern.

Bushnell instructed Alcorn to create instructions that would be printed on the cabinet to tell players how to operate the game. They had to be short and snappy, so Alcorn came up with “Avoid missing ball for high score.” Alcorn likes to joke that the phrase, which has taken on a life of its own in popular culture, will be carved on his tombstone.

At first, public response to Pong wasn’t astonishing. In the bar, the Pong unit sat beside a Computer Space machine, illustrating that the video game concept wasn’t completely new. But as more people began to play Pong, word spread throughout the area, and soon people were lining up outside Andy Capp’s at 9 AM in the morning just to play the new game. The bar owner had never seen anything like it — people were streaming into the bar not to buy alcohol, but to play a game!

Unintentionally, Pong carried with it an extra component that made it popular with the bar crowd: it didn’t feature a single player mode. That made it a social phenomenon that could be enjoyed between two friends or complete strangers, and it was simple enough to be played by young or old, drunk or sober.

The game was so popular, in fact, that it soon ran into problems. First, the consumer grade potentiometers used in the control knobs wore out. Alcorn sought out military grade pots so they could withstand the abuse of constant turning, day in and day out.

Then about two weeks into the trial run, Alcorn received a call in the middle of the night reporting that his Pong machine wouldn’t start a new game. He rushed over to fix the machine, then opened up the coin box to trigger a free game for troubleshooting. Quarters spilled out of the box and across the bar room floor. It was so stuffed with quarters that the mechanism had jammed.

For a young company like Atari, it was a good problem to have.

Handling Bally

With income streaming in from the Andy Capp Pong machine, Atari began to realize it had a hit on its hands. The trio hand built 12 additional Pong units and placed ten of them in operating locations to bring in some extra money. In the arcade industry, success is measured by the almighty quarter, so Bushnell had no problem temporarily putting his plans for a driving game on hold.

In early October 1972, Bushnell flew to Chicago and presented Pong as the videogame that would fulfill Atari’s contract. The game had been so successful that Bushnell reported a third of its actual earning power in fear that Bally wouldn’t believe the real numbers.

In early October 1972, Bushnell flew to Chicago and presented Pong as the videogame that would fulfill Atari’s contract. The game had been so successful that Bushnell reported a third of its actual earning power in fear that Bally wouldn’t believe the real numbers.

After his return, the coin-op giant dragged its feet in giving Atari an answer. As Bushnell and Dabney waited, they got anxious: the coins kept piling in from their Pong machines, and they knew that the game could be wildly successful. Bally just wasn’t seeing it.

Unfortunately for Atari, since Pong had been developed with Bally’s money — $24,000 of it — Bally technically owned the game. Atari couldn’t sell it to another company, and they couldn’t legally produce it themselves unless Bally formally rejected it.

“Nolan, Al and I were sitting there trying to figure out what to do, not getting any response from Bally,” recalls Dabney. “And I said, ‘We got to decide: either we go into manufacturing ourselves, or we go home. And I don’t want to go home.'”

According to Dabney, Bushnell and Alcorn were reticent to go into manufacturing, but they had no choice. Dabney hatched a plan to get out of the Bally deal. He carefully crafted a letter to the coin-op maker asking that Pong be rejected and released from the contract.

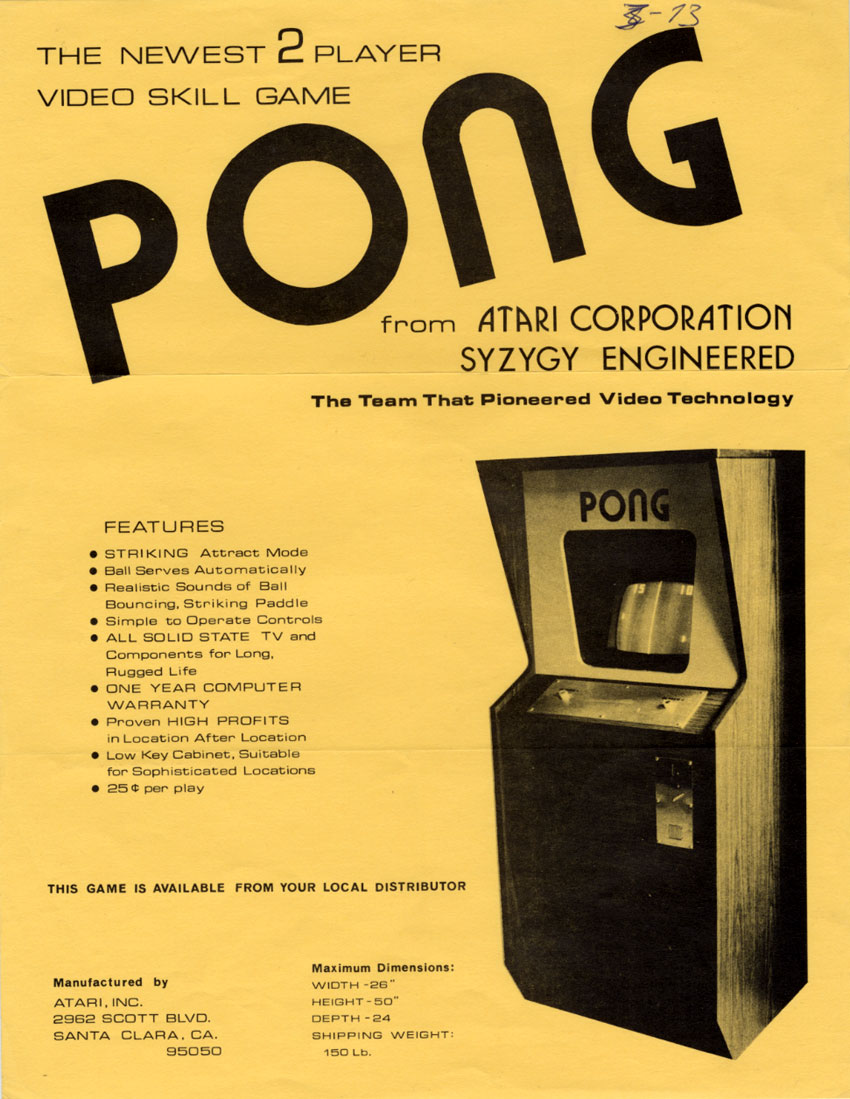

While they were waiting for a response, Dabney drew up plans for the production Pong cabinet (a simple wooden box with yellow trim) and ordered 50 of them from a local cabinet maker. Alcorn designed a PC board and made provisions to have it manufactured while also acquiring the necessary components.

At that time, Atari pulled in significant income (in the form of quarters) from its arcade games — about $6000 a week from the ten Pong machines alone. But the firm didn’t have quite enough to cover the cost of all the parts. Dabney reached into his personal savings and purchased 50 Hitachi black-and-white TV sets for the first round of Pong machines.

Not long after the purchase, Atari heard back from Chicago. Bally agreed to release Pong from the contract, and Atari was free to market the game on its own. The news simultaneously thrilled and frightened the makers of Pong.

Manufacturing Pong

As the 50 cabinets arrived in early November, Atari began hiring local workers to help put the machines together. With Atari having no prior manufacturing experience, the production of the first few runs of Pong machines proved to be very much an exercise in trial and error.

When it came time to sell the machines, Atari had to determine a price. They knew it had to be under $1000 to be competitive in the market, and the machine cost about $300 in parts to build. One day, Dabney looked out the window and saw “963” on a car license plate, and it clicked. The price would be set at $963 per machine.

When it came time to sell the machines, Atari had to determine a price. They knew it had to be under $1000 to be competitive in the market, and the machine cost about $300 in parts to build. One day, Dabney looked out the window and saw “963” on a car license plate, and it clicked. The price would be set at $963 per machine.

One day, as the first 50 units were being constructed by Alcorn and Dabney, Bushnell stood by passively and watched the process. Dabney looked up and said, “What are you doing? You’ve got to go sell these things.” According to Dabney, Bushnell turned white as a ghost. He walked to his office reluctantly, as if he were facing an impossible task.

An hour and a half later, Bushnell returned, dumbfounded. He had just sold 300 Pong units, sight unseen, to three different customers.

To cover the cost of the additional units, Atari obtained a line of credit from a local bank. Then Dabney ordered up 50 more cabinets. The young company was flying by the seat of its pants with little planning or foresight. A few days later, the cabinet maker delivered the units, and Atari ran out of space. They had no place to store them all.

Serendipity would be at their side however, as that very same day, someone at Atari noticed that their neighbors in their office complex had moved out unexpectedly the night before. Dabney took a sabre saw and cut a hole in the wall, walked through, and unlocked the back door — instantly doubling the company’s square footage. They settled the bill with the landlord later.

Even with that extra space, as word of Pong spread, Atari realized it would be needing much more room. They rented an empty roller skating rink nearby and hired even more workers, picking them up anywhere they could find; some from off the street, and some from unemployment lines.

These new workers, poorly screened, brought with them a new set of challenges. Some used illegal drugs on the manufacturing floor, and some stole the company’s TV sets. Atari was clearly learning as it went along.

Attack of the Clones

Only a month out of the gate, the genie was out of the bottle, and Atari had trouble keeping up with demand for Pong. “We did no marketing for that game,” recalls Dabney. “It spread by word of mouth.”

As it turned out, other companies would be happy to fill the need.

When Pong machines would break, many operators would send their Pong boards back to Atari so Alcorn could fix them. Only a few months after the game’s launch, Alcorn started noticing boards coming back in that had obviously not originated from Atari.

When Pong machines would break, many operators would send their Pong boards back to Atari so Alcorn could fix them. Only a few months after the game’s launch, Alcorn started noticing boards coming back in that had obviously not originated from Atari.

Enterprising companies around the US had taken Pong’s main circuit board and copied it directly, manufacturing clones with the exact same components in the exact same places, then passing it off as their own product under a new name.

Soon, dozens of Pong-like games flooded the arcade amusements market, and most of them were direct copies of Atari’s work. Bushnell was furious, but with Atari at full production capacity, Atari soon realized that cloners were not actually stealing Atari’s business.

“We were selling as many as we could make,” recalls Alcorn, “But we couldn’t sell as many as the market wanted, so these other guys popped up and filled the need.”

In some ways, the cloning was even good for Atari. The drastic explosion of Pong clones assured that the video game phenomenon spread faster than Atari could have managed alone, vastly expanding the demand for new video games.

The effect wasn’t limited to the United States: Pong soon spread overseas to Europe and Asia and provided the spark that launched hundreds of independent video game companies around the world.

Legacy

Ultimately, Atari sold anywhere between 19,000 and 35,000 Pong arcade machines (depending on who you ask), providing necessary capital to fuel the growth of Bushnell and Dabney’s company. Other games followed, but few were as popular as Pong.

In the face of the endless Pong clones, Bushnell decided that the only way to stay competitive was to innovate. At first, Atari released Pong derivatives like the four player Pong Doubles, then they moved on to different game styles like Space Race, Gran Trak 10 (Bushnell finally got his driving game), and Breakout. Competitors — especially those from Japan — followed with their own original titles, and the industry would never look back.

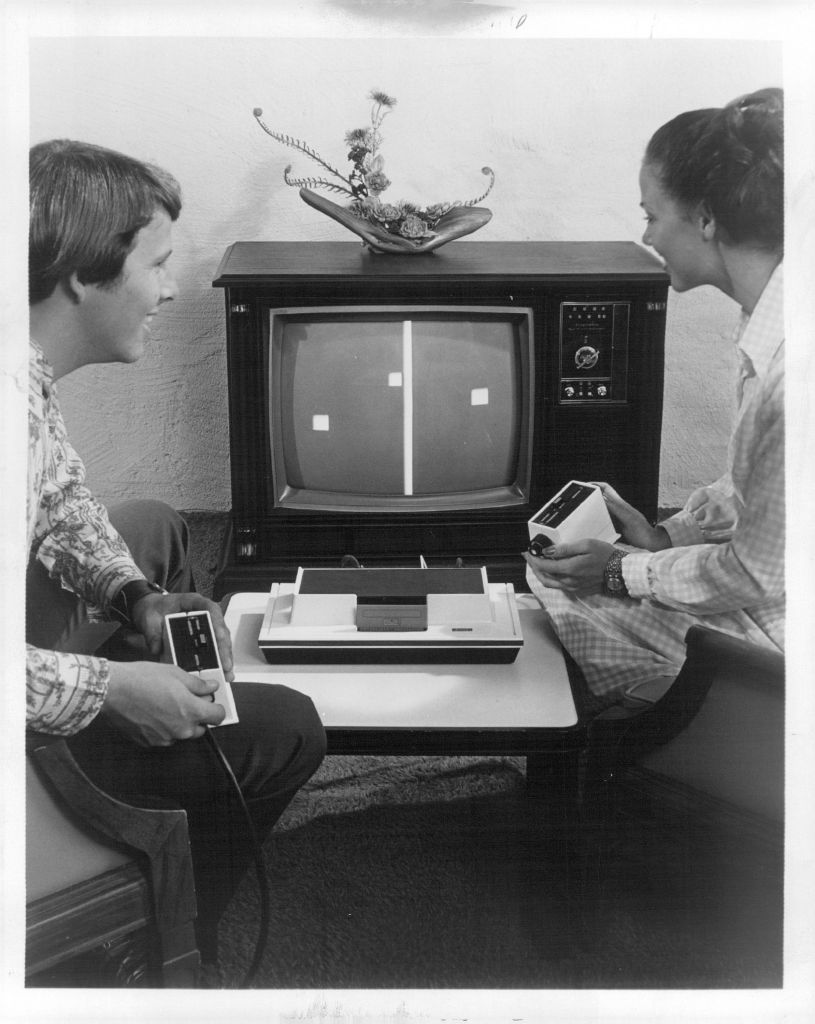

In 1975, Alcorn and fellow Atari employee Harold Lee designed a home console version of Pong, which set off a clone battle in the home space with a fervor that the Odyssey clearly hadn’t. In a sense, the astounding success of Pong launched both the arcade and home video game industries, even though the game wasn’t the founding product of either.

In 1976, Magnavox brought suit against Atari for patent infringement, and instead of fighting a costly court battle, Atari settled with Magnavox, acquiring a relatively inexpensive license to the patents and clearing the way for future innovation.

And innovation was to be had in spades, as Atari brought video games into the mainstream through its continued coin-op hits and its cartridge-based VCS game console, released in 1977.

All of that because three guys wanted to play games a little differently. Happy 40th birthday, Pong.

Sidebars

Too Many Quarters

Dabney recalls how he and his daughter would drive around to the Atari’s operating locations and collect all the quarters from their arcade machines. They would place all the quarters in a briefcase and take them home to roll them up for deposit. One day, his daughter dropped the briefcase on her foot. When she went to school, kids asked her what happened. She said, “I dropped a bunch of quarters on my foot.”

Pong on the Radio

Early on, Atari encountered a significant problem with Pong after receiving a complaint from a Nevada sheriff’s department. “They’d be driving and have their radio on,” recalls Dabney, “and all they could hear was the ‘ping, ping, ping’ from the Pong games in the bar down the road.” Improperly shielded, the machines’ circuitry would emit radio signals every time the ball bounced off a paddle. Alcorn devised a solution to the problem that blocked the interference, and Atari sent out patch kits to fix Pong units in the field.

Atari Obscured

Originally, Atari’s business plan was to design games and license them out to other manufacturers, similar to what Syzygy did with Nutting Associates. So if Bally had accepted Pong as the game to fulfill it’s contract, it is likely that Atari would have never gone into the manufacturing business itself. Atari would not be the household name is today.

Sources

- Telephone Interview with Alan Alcorn (26 September 2012) on Pong

- Telephone Interview with Ted Dabney (5 October 2012) on Pong

- Telephone Interview with Nolan Bushnell (11 November 2011) on Computer Space

- Video of original Pong arcade machine in action: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k0oAs5JTqCk

- Ping-Pong Origin: http://www.pingpong.com/

- General Info on Ralph Baer / Bill Rusch / Odyssey: Video Games Turn 40 (1UP, 2007): http://www.1up.com/features/videogames-turn-4

- General info on Pong History: http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/3900/the_history_of_pong_avoid_missing_.php

- Pong info at Pong-story.com: http://www.pong-story.com/arcade.htm