Eric’s Look at Trippy Computer Games

Tuesday, September 19th, 2006 Back in the good old days of computer gaming (we’re talking late-80’s to mid-90’s here, folks), one thing that could be said about the games market is that it was a crap shoot. Before the advent of the Internet, the few dead-tree review magazines couldn’t keep up with the number of newly-released titles, and computer game companies didn’t seem to take advertising very seriously. This meant that the chances of knowing the details of a game before purchasing it were pretty slim. Usually, all a gamer had to go on was the box copy, and whatever word-of-mouth could be picked up while hanging out at the local Babbage’s.

Back in the good old days of computer gaming (we’re talking late-80’s to mid-90’s here, folks), one thing that could be said about the games market is that it was a crap shoot. Before the advent of the Internet, the few dead-tree review magazines couldn’t keep up with the number of newly-released titles, and computer game companies didn’t seem to take advertising very seriously. This meant that the chances of knowing the details of a game before purchasing it were pretty slim. Usually, all a gamer had to go on was the box copy, and whatever word-of-mouth could be picked up while hanging out at the local Babbage’s.

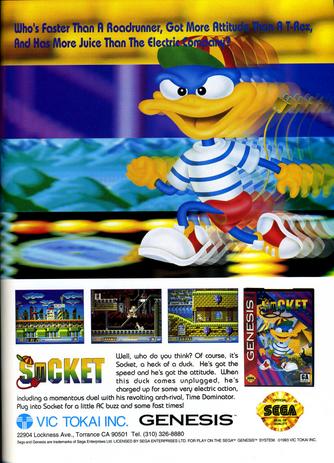

Buying a game could be a gamble, pure and simple. Sure, Origin was a safe bet for action or role-playing, and Sierra was the uncontested king of the adventure genre, but so many smaller companies were trying to make it big that it was impossible to know exactly what would be on the shelf on any given day. Sometimes, a search though the $5 rack would reveal an unlikely-sounding game written by two guys in a smelly basement, only to be unmasked later as a true gem of programming skill. More often, a slick-looking box with beautiful images and promising descriptions would turn out, when unboxed at home, to fall somewhere between maddeningly dull and outright unplayable (I’m looking at you, Rocket Jockey). But rarely, very rarely, a game would crop up that would cause an immediate and almost-universal reaction among gamers: “What were those guys smoking, and where can I get some?”

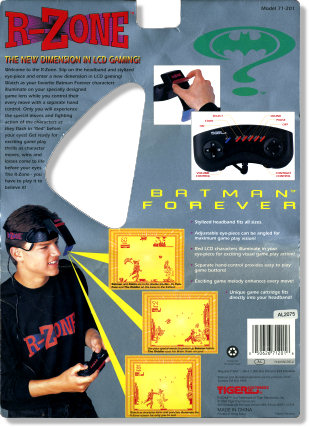

Way back in the land before time (1995), when a little ole company you might have heard of called “Nintendo” was tinkering with its worst gaming experiment ever (

Way back in the land before time (1995), when a little ole company you might have heard of called “Nintendo” was tinkering with its worst gaming experiment ever (

[ In this article, I’m testing a new image preview method. You can see a larger version of most images by hovering your mouse cursor over an image. Please let me know if you encounter any problems with this. — The Editor ]

[ In this article, I’m testing a new image preview method. You can see a larger version of most images by hovering your mouse cursor over an image. Please let me know if you encounter any problems with this. — The Editor ]

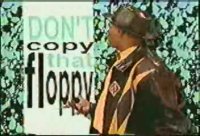

The early copy protection schemes were much more analog than digital, and tended to fall into two categories: code wheels and manual lookups. That’s right, they used documents and devices that were physically separate from the program. While the games themselves were easy to duplicate, copy protection (C.P.) implementations weren’t. Moving parts, dark-colored pages, esoteric information scattered throughout a manual all meant that photocopying (when possible) could be prohibitively expensive. And without a world-wide publicly available Internet, digital scans and brute-force cracking programs were almost unheard of. For the most part, the C.P. methods were an effective low-tech solution to a high-tech problem.

The early copy protection schemes were much more analog than digital, and tended to fall into two categories: code wheels and manual lookups. That’s right, they used documents and devices that were physically separate from the program. While the games themselves were easy to duplicate, copy protection (C.P.) implementations weren’t. Moving parts, dark-colored pages, esoteric information scattered throughout a manual all meant that photocopying (when possible) could be prohibitively expensive. And without a world-wide publicly available Internet, digital scans and brute-force cracking programs were almost unheard of. For the most part, the C.P. methods were an effective low-tech solution to a high-tech problem.