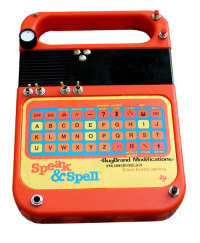

VC&G Interview: 30 Years Later, Richard Wiggins Talks Speak & Spell Development

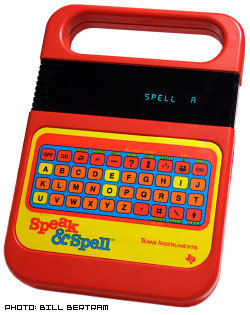

December 16th, 2008 by Benj Edwards Thirty years ago last June, Texas Instruments introduced Speak & Spell at the Summer Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago. This electronic spelling teacher for kids broke new ground by speaking out words via built-in voice synthesis — a world-first for a consumer product.

Thirty years ago last June, Texas Instruments introduced Speak & Spell at the Summer Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago. This electronic spelling teacher for kids broke new ground by speaking out words via built-in voice synthesis — a world-first for a consumer product.

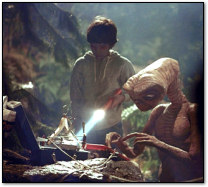

By Christmas 1978, the iconic orange and yellow device hit stores with a suggested retail price of $50 (US). TI’s new toy sold very well and became a media sensation, landing on magazine covers and eventually making an appearance as a key prop in a major Hollywood film, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.

Intending to write an article about Speak & Spell’s 30th anniversary last July, I conducted an email interview with Richard Wiggins, a member of the original Speak & Spell development team. Wiggins is notable for co-designing speech synthesis techniques capable of being mass-produced in an inexpensive consumer product, which was no minor task in 1978.

I wanted to share my interview with Mr. Wiggins before the year is out, as it’s not only more relevant during 2008, but it also might be of interest to historians some day. In the mean time, I hope you enjoy reading it.

Personal History

Benj Edwards: Where and when were you born?

Richard Wiggins: I was born in Baton Rouge, Louisiana in the Summer of ’42. My Mom and Dad had met at LSU and my Dad taught Journalism at LSU for many years.

BE: Can you give us some background on your career before you joined Texas Instruments?

BE: Can you give us some background on your career before you joined Texas Instruments?

I studied Mathematics at LSU, then left Louisiana, worked for the DoD in Washington and earned a MS in Math from American University.

Then I went to a company called MITRE Corp (a non-profit, FCRC – Federal Contract and Research Center) in Bedford Mass, which had an excellent “Staff Scholar” program which enabled staff members to earn advanced degrees. I was awarded a scholarship and attended Harvard where I earned a PhD in Applied Mathematics. MITRE worked mostly on radar and communication systems for the Air Force and I became involved in low bit rate voice compression for secure communication systems.

At MITRE we were developing software and DSP (digital signal processing) algorithms for processing digitized voice signals. The computers we were using for voice processing were getting smaller and smaller and and the possibilities for new and exciting applications involving real time speech processing for applications seemed like an exciting field to explore further.

After a few years working closely with speech research teams at Lincoln Laboratories and the Air Force Laboratories at Hanscom AFB, also in Bedford, I took the opportunity to join the Central Research Laboratories at Texas Instruments in Dallas, Texas. This was an opportunity to do further work in speech research, and I saw it as a chance to apply some of my newly learned skills at a company that at that time was involved in consumer products, military products, and computer systems as well as several other business areas. Besides, my wife (also from Baton Rouge) and I had lived on the east coast for 13 years, and Dallas was much closer to family.

As you can see from the above, I was an applied mathematician with experience in numerical algorithms working in what was then the rather new area of processing speech signals with digital algorithms. TI’s Speech Research group in the Corporate Research Laboratories gave me the opportunity to keep working in this area and I was intrigued by the thought that semiconductors could do some of this processing in real time.

BE: When did you first start working at Texas Instruments, and how did you get the job?

BE: When did you first start working at Texas Instruments, and how did you get the job?

RW: I started work at Texas Instruments in November of 1976 and, as described above, I was to work on a government funded research program to look at implementing a voice coder in experimental semiconductor technology (CCDs).

There were only a few companies doing interesting research in speech processing at that time and TI seemed to have a really good R&D program. They hired me because of a government funded program to explore implementing a channel vocoder in the new (at that time) CCD (charge-coupled device) technology.

Speak & Spell History

BE: Under what circumstances did the Speak & Spell project get started?

RW: Following the success of the product called “The Little Professor,” several sessions were held to brainstorm future possible products.

BE: Who came up with the idea for the Speak & Spell?

RW: Generally, Paul Breedlove is credited with of a learning aid for spelling.

BE: What was the ultimate goal or aim of the Speak & Spell?

RW: To serve as a learning aid for spelling…right away, it was clear that it should be capable of “calling out” the spelling words.

BE: When did Speak & Spell development begin, and where did development take place?

RW: It began in November of 1976, when Paul Breedlove won a small amount of financing to try to prove the concept of a learning aid for spelling. Paul’s suggested name was “The Spelling Bee.”

BE: How big was the Speak & Spell development team, and who else was involved?

BE: How big was the Speak & Spell development team, and who else was involved?

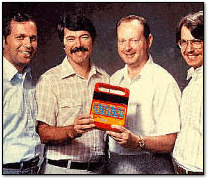

RW: Initially, there were only a very few people involved. At the initial meeting in November, Paul Breedlove came over to the research Labs with Gene Frantz and Larry Brantingham from the Consumer Products Group. The result of that meeting was that I was to propose a technique for generating the speech in the product. The challenge was that it had to be solid state (no pull strings!), cheap (meaning it used a low cost semiconductor technology), and the speech had to be good enough so that the user could understand the word out of context — a little bit harder than using a word in a sentence. Larry was a circuit designer and was tasked to determine if what I came up with could be implemented in an integrated circuit. Larry and I spent time together discussing various strategies, and Gene Frantz, who eventually became the project manager, kept the overall design moving forward.

As the program moved forward during 1977, additional people kept being added to the project. It was amazing to me how many people eventually become involved. [There were] people working on which spelling words to chose, what the product should look like, what it should be called, where it would be manufactured, and how it was to be marketed.

BE: Describe for me, if you could, the role these people played in the development of the Speak & Spell:

Paul Breedlove

RW: Originated the idea of a learning aid for spelling.

BE: Gene Frantz

RW: Responsible for the overall product design; spelling words, case design, display, and operation.

BE: Larry Brantingham

RW: IC designer.

BE: What was your official role in the Speak & Spell’s development?

RW: Voice processing algorithms.

BE: What was your biggest contribution to the project?

RW: I promoted the choice of linear predictive coding to generate the speech signal from a small amount of data. Today, the speech could easily be recorded and stored in large digital memory chips. But in 1976, memory chips were not capable of storing that much data. We considered generating the speech from phonemes or sound fragments but the speech quality was not sufficient. A digital filter could be used and the time varying coefficients could be stored in memory but the amount of computations involved seemed too great.

Also, some kind of speech elements shorter than words were considered, but it appeared that the amount of computer processing to prepare data to drive the speech synthesizer would be too time consuming, and the resulting system would be very complex. We needed something simple to generate the speech sounds, and a preparation system for the data that wouldn’t be too complicated to execute.

BE: If you could, describe for me the atmosphere and general feeling of your office during the creation of the Speak & Spell.

RW: I would say that everyone worked extremely hard on the program. One of the reasons was that when we finally started to realize how simple it would be to do this, we began to believe that we couldn’t possibly be the only people who had thought of doing this. We were very much afraid that someone else would “beat us to the punch.” As a result, we put lots of emphasis on the schedule.

BE: What obstacles, if any, did you face while developing the Speak & Spell?

RW: At first, some of the management obviously didn’t think it could be done, and occasionally, well-respected members of the technical community would show up and ask for a review of what we were doing. Later, it seemed obvious that they were supposed to be checking up to see if we really knew what we were doing.

BE: Who developed the TMS5100/TMC0281 speech synthesis chip for the Speak & Spell?

RW: I worked closely with Larry to design a processing architecture that could perform the necessary computations in a dedicated architecture. After we did the basic design, other researchers worked with me to develop the analysis procedures to determine the synthesizer control data, and other IC designers worked with Larry to complete the design. However, most of the patents for the speech chip are in my name and Larry’s name.

BE: How did you manage to create a synthesis chip cheap enough for mass production in a consumer toy?

BE: How did you manage to create a synthesis chip cheap enough for mass production in a consumer toy?

RW: [TI’s Consumer Products division] was designing many dedicated IC circuits for use in consumer products. Many of these IC’s were designed in PMOS, a semiconductor technology that was low cost.

BE: How many words was the Speak & Spell capable of saying?

RW: About 200.

BE: From what I understand (and I might be wrong), the Speak & Spell was never capable of saying any arbitary word that one might type into the unit, but instead was limited to a set vocabulary. Why is that?

RW: Basically, the control data for the speech chip has to come from somewhere. We generally stored strings of data that corresponded to a particular word. Patterns for new words were generated back in the laboratory — sometimes by experimenting with data, but certainly the best results were obtained by large computer programs that analyzed real speech data and determined data patterns and strings of data that, when applied to the synthesizer, resulted in words that could be easily understood and sounded very much like the original speech.

However, a substantial amount of hand editing was used. This did turn out to be very time consuming and wasn’t always successful. Sometimes, we needed a word and could construct it from other pieces of speech data. Other times it required collecting actual speech data and analyzing it. We did choose a particular person whose voice we collected on tape, digitized hundreds of utterances, set up an editing station to listen to each word, and generally play with the parameters until the voice sounded suitable. It turned out that that there was so much data, and it required so many individual decisions, that it consumed incredible amounts of time and was difficult to do. Actually, this turned out to be something of a huge challenge for future products and dogged the technology for many years.

BE: Did the Speak & Spell development team ever consider using anything other than the TMS1000 chip for the heart of the Speak & Spell?

RW: At the beginning of the program, alternative approaches were frequently proposed. Researchers using the CCD technology thought it should have been used, but it was too expensive. Some thought that a general programmable chip should have been used, but none existed at that time that could do the necessary computations.

BE: Can you share any funny, interesting, or unusual anecdotes about the Speak & Spell that we haven’t covered already?

RW: The initial focus groups were interesting: it was never clear that they really understood how appealing a talking product would be to a small child. The first demonstration to the president and the board of directors was interesting — they thought it was being sold too cheap!

[I also remember] seeing people in stores experience it for the first time, visiting government labs and technical conferences, and our press tour to New York.

Release and Impact

BE: What was the public & press reaction to the Speak & Spell when it first debuted?

BE: What was the public & press reaction to the Speak & Spell when it first debuted?

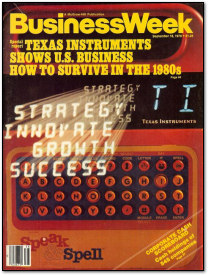

RW: Amazing…see the cover of Business Week.

BE: How many units of the Speak & Spell did TI sell? Was it considered a success for Texas Instruments?

RW: I don’t know how many they sold, but it was sold in many countries and lots of versions: Speak and Read, Speak and Math, etc.

BE: Did you ever plan any interesting add-ons or upgrades for the Speak & Spell that were never released?

RW: We did an interesting unit for the TI home computer. We wanted to build products that would teach writing to children, and teach songs, but we were never able to sell the ideas.

BE: Besides the Speak & Spell, did you work on any other major projects at TI?

RW: Voice coders for military products. This device was basically a cell phone done in the 70’s. We also did a voice verification system for Sprint. Also, we designed a really neat talking doll named Julie that also had speech recognition.

Legacy & The Present

BE: How has being a designer of the Speak & Spell changed or influenced the course of your life?

RW: Wow…lots of recognition and praise. Even my grandchildren mention it sometimes.

BE: Are you aware of people “circuit bending” the Speak & Spell? What do you think about the process and the artform?

BE: Are you aware of people “circuit bending” the Speak & Spell? What do you think about the process and the artform?

RW: Yes, I have seen them on eBay. It makes me think of the games we used to play with the computer simulation of the chip we designed. Of course, we were able to get to the actual control parameters and could vary parameters corresponding to pitch and vocal tract shape. By scaling, we could change the voice to a female sounding voice, or a whisper, or we could change the speed of the speech. It was actually lots of fun, and we thought about putting some additional options in the product, but the product designers in Consumer Products were very concerned that the product be presented as a Learning Aid and not a toy.

BE: How does it make you feel to see people using the Speak & Spell in new and interesting ways?

RW: Sometimes I think it could be art. An artist visited me once, I think the name was Newhouse. He was an acoustic artist and I think he was interested in providing background noise for various environments. I don’t think that he was in a position to understand the possibilities and how they could be used.

BE: What are you up to these days? Do you do any electronics tinkering or design in your spare time?

RW: I am fully retired at the age of 65 (soon to be 66!) and have moved from Dallas to San Antonio to live around the corner from my daughter and her family. Yes, I do tinker quite a bit. I love my Mac, Apple TV, etc., and end up spending lots of time with them. I have taught some at UTSA, but teaching is quite time consuming.

BE: Do you have any thoughts or comments you’d like to share about the Speak & Spell’s 30th anniversary?

RW: I recently gave a “career lecture” to 8th grade students and it was a real kid because one of the teachers remembered buying the product when it came out. Most of the kids today don’t fully understand the product, the challenge of designing it, and the impact that it had (the Speak & Spell made it into museums and movies: e.g. E.T.).

December 16th, 2008 at 10:22 pm

Fascinating! Great article as always, Benj! I bet this guy is responsible for that digital voice encryption the FBI used, and yet he made the Speak And Spell! Hardcore. :3

Also why does the Speak and Spell at the top ask you to spell “A”? A is not very hard to spell. XD

December 16th, 2008 at 10:55 pm

I have very fond memories of my Speak and Read. Sometimes the synth voices run through my head (e.g. “WORD ZAP…. LEVEL ONE”). 🙂

December 26th, 2008 at 6:51 pm

Great interview!

@Kitsunexus: Actually “Spell A” designated the difficulty level. ‘A’ was the easiest, ‘D’ was the hardest.

December 26th, 2008 at 11:48 pm

I credit this invention for my english proficiency.

If i had to name one invention that really made a difference to my life,this would be it.

Thank you, Mr Wiggins!

December 27th, 2008 at 9:49 am

My parents recently came and brought my old speak and spell – while my daughter is a tad young for it, she loves playing with it. We put the batteries in and out came that familiar startup sound, along with the memories.

December 28th, 2008 at 6:07 am

Excellent article! Although I never owned one, I was deeply impessed by the technology at the time. TI sure had great R&D. I think they still do.

December 28th, 2008 at 10:25 pm

I remember a friend had one, and we would giggle as we typed profanities on it.

June 17th, 2009 at 12:16 am

Hey! I had this when I was a kid!!!

September 13th, 2010 at 7:44 am

Back around 1978, I was an associate editor at Electronic Design magazine, and they assigned me to write up Speak & Spell. We debated for a short while, and agreed that it was OK to call it a “breakthrough”. Even as jaded EE types, we were quite impressed by it, pleasantly surprised to see what could be done affordably by the technology of the time. This is the first time I knew about the people involved; it was delightful to read. Many thanks!

Indeed, it’s a great pity that almost nobody realizes first, how essentially sophisticated internally it is, and second, how advanced its technology was for its time. (Shades of the Amiga computer!)

Fwiw, only a few minutes ago did I learn (from Wikipedia) what LPC is and how it works.

Best regards,

[nb]

July 15th, 2011 at 8:06 am

I had a tough time learning to read let along spell. I grew up in a Latin family thus making it hard to learn two languages simultaneously. I am 28 years old now, I had my first speak and spell by the ending of 1st grade or beg of 2nd grade and let me tell you- HALLELUJAH!!!! I know this is a really old article but I have been searching ALL over the net for this device cause I want to buy it for my daughter (i know she is only 7 months) but it made such a HUGE impact in my life, I LOVED my speak and spell, I had to give it away by force cause after a while it drove the family crazy =) Seeing it brings tears to my eyes! ***(((((((HUGS))))))***

July 23rd, 2014 at 3:19 am

Whose voice was recorded? The article mentions ‘a person’ but does not say who…

October 29th, 2014 at 4:25 pm

In a 2009 interview, Gene Frantz mentioned that the voice was that of a Dallas radio announcer, but he didn’t recall the name. Originally, they wanted a female voice, but the formants for a female voice were too complex for the processor that they were using in 1978.

October 29th, 2014 at 6:30 pm

Great detail, David. Thanks for commenting.

April 30th, 2015 at 12:12 pm

The name of the radio announcer was Hank Carr. I wonder where is is now. I spent many hours listening to his voice and learning how to repeat his inflection. He had really great pitch! I do remember attending a professional basketball game in Dallas once and he was announcing the game. I recognized his voice right away.

March 21st, 2018 at 2:38 pm

I found this fabulous history to satisfy my curiosity about the nature of the speech synthesis in the Speak & Spell.

My curiosity was stoked because I was just playing with the 1979 US Speak & Spell,

emulated at a chip level!

https://archive.org/details/hh_snspell

This MAME-based emulation runs in modern browsers via JS/WebAssembly, no plugins no Java etc.

I am truly amazed that the emulation sounds exactly as I remember from my own childhood. I was exactly the demographic for this product and loved it when it was released. Like my TI calculators that followed, the cutting edge was very exciting…