Why the Apple II Didn’t Support Lowercase Letters

Tuesday, September 8th, 2020[Editor’s Note: I recently asked Steve Wozniak via email about why the original Apple II did not support lowercase letters. I could have guessed the answer, but it’s always good to hear the reason straight from the source. Woz’s response was so long and detailed that I asked him if I could publish the whole thing on VC&G. He said yes, so here we are. –Benj]

In the early 1970s, I was very poor, living paycheck to paycheck. While I worked at HP, any spare change went into my digital projects that I did on my own in my apartment. I was an excellent typist. I was proficient at typing by touch using keypunches with unusual and awkward special characters — even though some used two fingers of one hand.

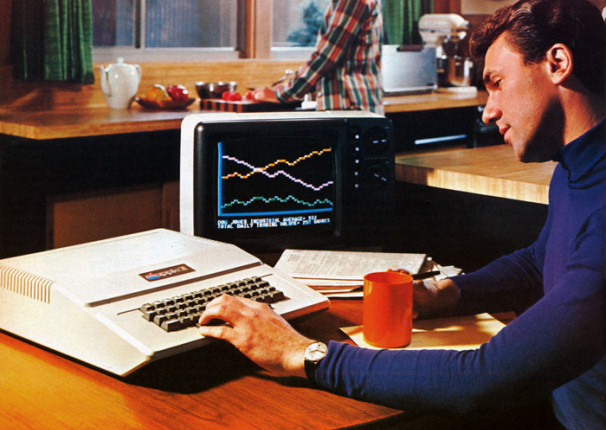

I saw a friend typing on a teletype to the six computers on the early ARPAnet. I had to have this power over distant computers too. After building many arcade games on computers, how to build it was obvious to me instantly. I’d create a video generator (as with the arcade games) and display text using a character generator chip. But I needed a keyboard.

I saw a friend typing on a teletype to the six computers on the early ARPAnet. I had to have this power over distant computers too. After building many arcade games on computers, how to build it was obvious to me instantly. I’d create a video generator (as with the arcade games) and display text using a character generator chip. But I needed a keyboard.

I’d show up at HP every morning around 6 AM to peruse engineering magazines and journals to see what new chips and products were coming. I found an offer for a $60 keyboard modeled after the upper-case-only ASR-33 teletype.

That $60 for the keyboard is probably like $500 today [About $333 adjusted for inflation — Benj]. This $60 was the single biggest price obstacle in the entire development of the early Apple computers. I had to gulp just to come up with $60, and I think my apartment rental check bounced that month — they put me on cash payment from then on. Other keyboards you could buy back then cost around $200, which might be $1000 or more now. There just wasn’t any mass manufacturing of digital keyboards in 1974.

So my TV Terminal, for accessing the ARPAnet, was uppercase only.

The idea for my own computer came into my head the first day of the Homebrew Computer Club.

The idea for my own computer came into my head the first day of the Homebrew Computer Club.

Maybe a year prior, I had looked at the 4-bit Intel 4004 microprocessor and determined that it could never be used to build the computer I wanted for myself — based on all the minicomputers that I’d designed on paper and desired since 1968-1970. But at the Homebrew Computer Club, they were talking about the 8008 and 8080 microprocessors, which I had not kept up with after my 4004 disappointment. I took home a data sheet for the 8008, based on a version of it from a Canadian company. That night, I discovered that this entire processor was capable of being a computer.

I already had my input and output, my TV Terminal. With that terminal, I’d type to a computer in Boston, for example, and that far-away computer, on the ARPAnet, would type back to my TV. I now saw that all I had to do was connect the microprocessor, with 4K of RAM (I’d built my tiny computer with the capability of the Altair, 5 years prior, in 1970, with my own TTL chips as the processor). 4K was the amount of RAM allowing you to type in a program on a human keyboard and run it.

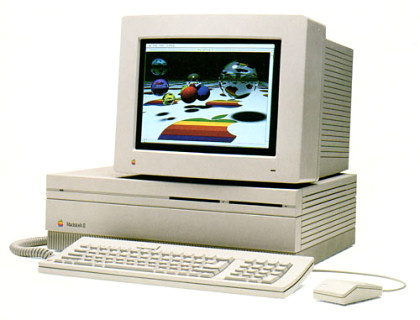

My computer wasn’t designed from the ground up. I just added the 6502 microprocessor and 4K DRAMS (introduced that summer of 1975 and far less costly than Intel static RAMs) to have a complete computer with input and output.

So the uppercase keyboard was not designed as part of a computer. It already existed as my TV Terminal.

I truly would have wanted lower case on a keyboard, but I was still totally cash strapped, with no spare money. After already starting a BASIC interpreter for my computer, I would have had to re-assemble all my code. But here again, I did not have the money to have an account on a timeshare service for a 6502 interpreter. The BASIC was handwritten and hand-assembled. I’d write the source code and then write the binary that an interpreter would have turned my code into. To implement a major change like lower case (keeping 6 bits per character in my syntax table instead of 5 bits) would have been a horrendous and risky job to do by hand. If I’d had a time-share assembler, it would have been quick and easy. Hence, the Apple I wound up with uppercase only.

I truly would have wanted lower case on a keyboard, but I was still totally cash strapped, with no spare money. After already starting a BASIC interpreter for my computer, I would have had to re-assemble all my code. But here again, I did not have the money to have an account on a timeshare service for a 6502 interpreter. The BASIC was handwritten and hand-assembled. I’d write the source code and then write the binary that an interpreter would have turned my code into. To implement a major change like lower case (keeping 6 bits per character in my syntax table instead of 5 bits) would have been a horrendous and risky job to do by hand. If I’d had a time-share assembler, it would have been quick and easy. Hence, the Apple I wound up with uppercase only.

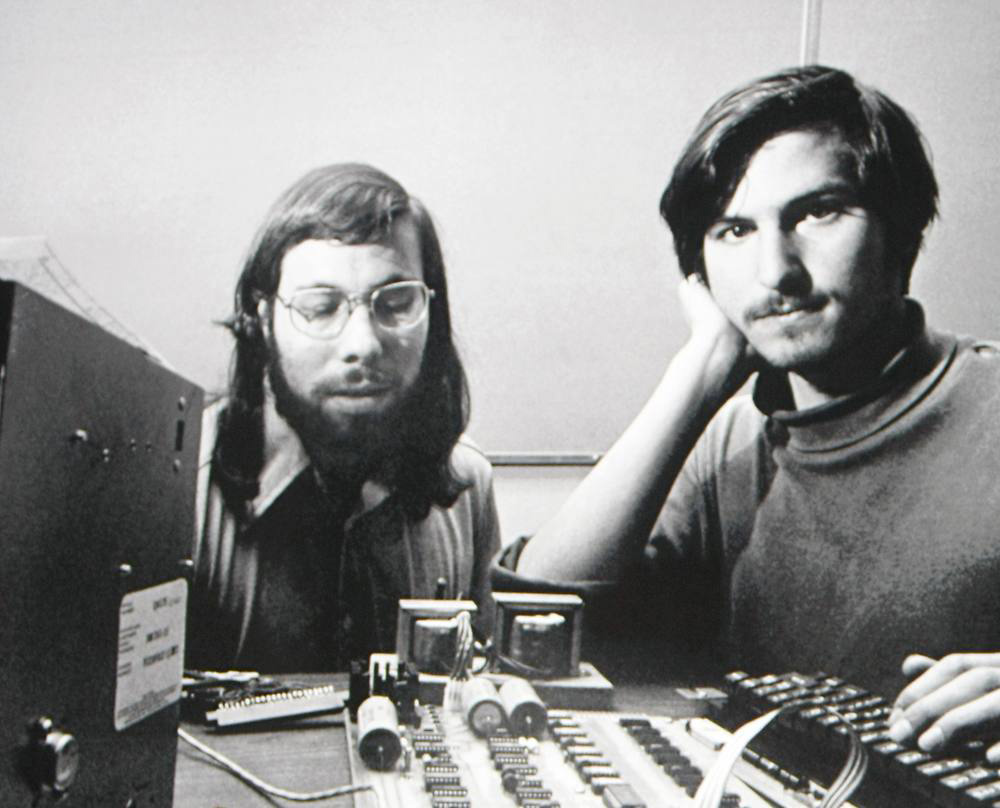

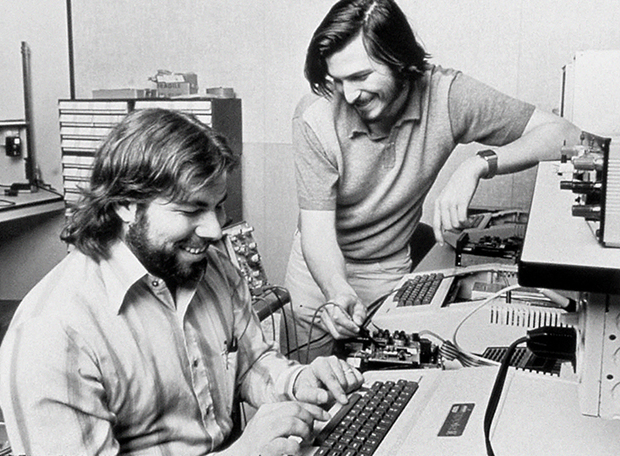

I discussed the alternatives with Steve Jobs. I was for lower case, but not for money (cost). Steve had little computer experience, and he said that uppercase was just fine. We both had our own reasons for not changing it before the computers were out. Even with the later Apple II (as with the Apple I), the code was again hand-written and hand-interpreted because I had no money. All 8 kB of code in the Apple II was only written by my own hand, including the binary object code. That made it impossible to add lower case into it easily.

So, in the end, the basic reason for no lowercase on the Apple I and Apple II was my own lack of money. Zero checking. Zero savings.

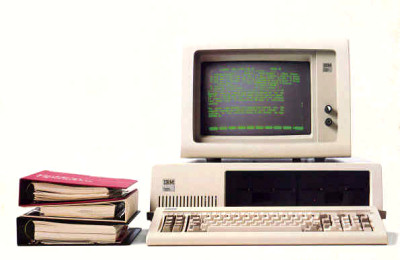

Much ballyhoo has been made, for example, about how IBM lost its grip on the PC’s direction as clones flooded the market. From a different perspective, that runaway-freight-train-of-a-platform is a success story for IBM.

Much ballyhoo has been made, for example, about how IBM lost its grip on the PC’s direction as clones flooded the market. From a different perspective, that runaway-freight-train-of-a-platform is a success story for IBM.

Tomorrow is Thanksgiving in the United States, which means we cook a lot, eat a lot, sleep a lot, feel uncomfortable around somewhat estranged relatives a lot, prepare to spend a lot, officially start Christmas a lot, and generally take it all for granted, despite the title of the holiday. In order to break with American tradition, I thought I’d offer a personal list of things that I think we — vintage computer and video game enthusiasts — should be thankful for. After all, these things let us enjoy our hobbies. Without them, we’d be collecting dirt and not even know what it’s called. Pay attention, my friends, as we start off serious-ish and degrade into something resembling silliness — but it’s all in the name of holiday fun.

Tomorrow is Thanksgiving in the United States, which means we cook a lot, eat a lot, sleep a lot, feel uncomfortable around somewhat estranged relatives a lot, prepare to spend a lot, officially start Christmas a lot, and generally take it all for granted, despite the title of the holiday. In order to break with American tradition, I thought I’d offer a personal list of things that I think we — vintage computer and video game enthusiasts — should be thankful for. After all, these things let us enjoy our hobbies. Without them, we’d be collecting dirt and not even know what it’s called. Pay attention, my friends, as we start off serious-ish and degrade into something resembling silliness — but it’s all in the name of holiday fun.